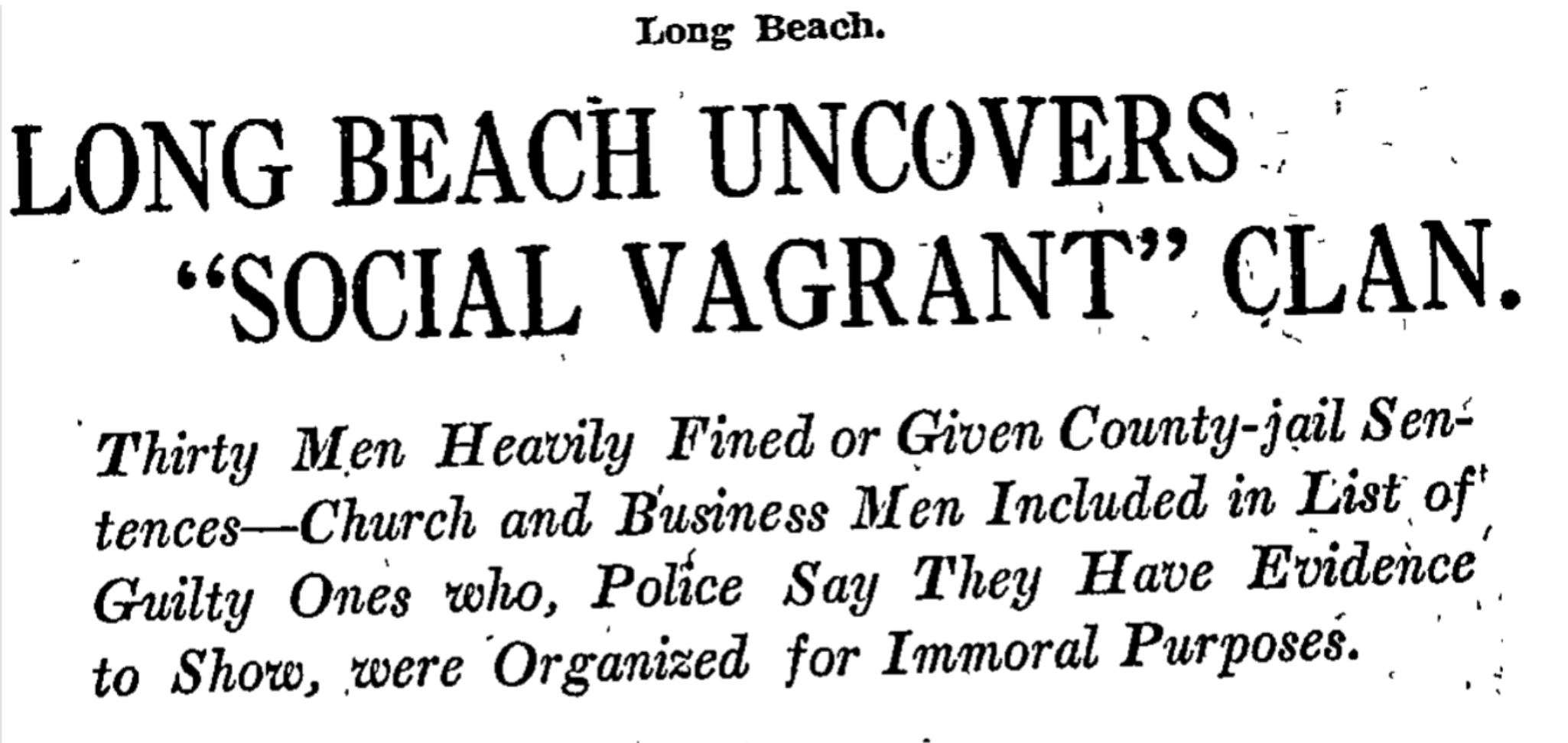

In the heavy heat of a Southern California summer in 1914, Long Beach launched one of the earliest known anti-queer crackdowns in U.S. history — a dark chapter known now, quietly, as The Long Beach Purity Raids. It didn’t make national headlines the way Stonewall eventually would. It wasn’t taught in history books or commemorated with a city plaque. It was swept under the rug, as so many queer stories have been — especially when they come from brown, working-class mouths.

But the truth is, these arrests were a coordinated campaign, fueled by moral panic and class prejudice, that shattered lives.

Over the span of just a few weeks, at least 31 men were entrapped and arrested in what authorities described as a campaign against “social perverts” and “degenerates.” Undercover police officers — some reportedly dressing in women’s clothing — posed in restrooms and alleyways near downtown Long Beach, trying to lure men into conversation or ambiguous gestures that could be twisted into charges of “lewd conduct,” “vagrancy,” or “immorality.” Most of the men arrested were working-class. Several were immigrants. Some only spoke Spanish. And none were safe.From the Los Angeles Times article dated May 21, 1914, titled “Vice Squad Makes Many Arrests”, we see the deeply dehumanizing language and methods used by police. Officers boasted of their “successful work in rounding up degenerates,” and described the use of plainclothes detectives to ensnare targets in what they labeled as a “moral clean-up” operation.

Here are just a few of the names recorded:

Domingo Arzate

Tomás Vargas

José Aguilar

Leonardo Alvarado

Henry Johnson

Ralph Gomez

Joe Rios

Frank Lopez

Albert Gonzales

Antonio Rodriguez

William Hart

Luther Kerns

Walter Stevens

Edward Mills

Charles Withers

Julius Mendez

Fred Jenkins

James T. Riley

Otto Schmidt

Benjamin Walker

In that same article, the paper notes that Domingo Arzate, described as a “Mexican laborer,” was convicted based solely on “indecent behavior” observed by a plainclothes officer in a public restroom — with no physical evidence, no witness testimony beyond that of the officer. He was sentenced to 90 days of hard labor in the county workhouse.

José Aguilar, according to the Times, was labeled “a chronic degenerate,” although there was no criminal record attached to his name in court records. The article brags about his swift conviction and notes that the courtroom “broke into laughter” as testimony was given. It also mentions that Aguilar was “likely to be deported,” as he was not fluent in English.

Leonardo Alvarado’s story is even more chilling. In the article from May 26, 1914, “More Immoral Men Arrested in Long Beach”, it states that Alvarado “was unable to explain himself clearly due to language issues,” and the judge proceeded without a translator. He was sentenced on the spot. The article smugly notes that Alvarado appeared “confused” and “pitiful.”

Joe Rios was reportedly forced to write a letter to his employer — dictated by the arresting officer — in which he had to confess the reason for his absence and his charges. While this specific humiliating tactic is paraphrased in the LA Times articles, it’s echoed more vividly in anecdotal historical accounts such as the Homestead Museum’s blog post on the raids, which recounts how law enforcement used public shame as a weapon beyond the courtroom.

Fred Jenkins, a Black man and porter at the time, was described in the Times coverage as “untrustworthy” and “familiar to police,” despite having no listed prior offenses. He received a harsher sentence than others arrested in the same week. Charles Withers, a railroad worker, and William Hart, a store clerk, were sentenced together after being arrested in a restroom near Pine Avenue. Their alleged “immoral behavior” was never clearly defined, but the court offered no defense or nuance — only sentencing.

These were not trials. They were public executions of dignity — carried out through humiliation, police entrapment, and media complicity.

And then… silence.

Their stories vanish from the record. No follow-up. No closure. No trace of what happened after their release. Their lives evaporated from public memory, not because they didn’t matter — but because they were never supposed to.

But there is one name we almost remembered — one man whose story flickered briefly in the public eye because the consequence was too final to ignore.

In a follow-up article dated May 23, 1914, the Los Angeles Times reported that one of the arrested men — a local banker — had died by suicide. Though the article withheld his name, likely due to pressure from his family or employer, it stated that he had taken his life after being publicly outed in connection with the Purity Raids. He was found at his home by a colleague. The newspaper described it plainly: he had “taken drastic steps” after his “disgraceful arrest.” There was no sympathy. No deeper questioning. Just a final sentence in a short column — another life ruined, then erased.

Unlike the other men whose names were broadcast without hesitation, the banker was given anonymity in death. Perhaps it was because of his class status, or his connections. But that final silence — even in print — does not protect him from being a part of this story. It underscores the stakes.

He was likely white, middle-class, respected. And yet the shame, the exposure, the loss of social standing, were too much. He was a casualty not just of police repression but of a culture that made queerness unbearable to live with.

His story reminds us: these raids didn’t just lock people up. They destroyed futures. They shattered families. They killed.

When I first found this story buried in scanned LA Times articles and an old museum blog, it hit like a punch to the chest. I throw LGBTQ+ community events in Long Beach. I organize queer meet-ups, food festivals, beach takeovers — all to celebrate queer & latino joy. But here, just blocks from where we now wave rainbow flags and blast pop divas by the shoreline, our queer ancestors were hunted.

“Every time we gather, every time we take up space loudly and publicly as queer people, we’re undoing some of the fear they tried to instill in us over a century ago. We’re saying: you tried to erase us. But we are still here.”

— Salvador Flores-Trimble, Playalarga Productions

We can’t just celebrate without remembering. The fight for queer liberation didn’t start at Stonewall, and it didn’t only happen in New York or San Francisco. It happened here. In alleyways behind 1st Street. In courtrooms that treated brown queerness as a disease. In Long Beach — a city whose queer legacy is far deeper, and more complex, than it wants to admit.

This isn’t just a story of loss. It’s a call for action.

Where is the memorial? Where is the mural, the historical marker, the community gathering to say their names aloud? Why is this history not taught in Long Beach schools, not acknowledged by local politicians who show up to the Pride parade every year?

Let’s tell it. Loudly. And not just in our queer spaces — but in our libraries, classrooms, and city council chambers. Let’s take their mugshots and turn them into portraits. Let’s throw parties that double as remembrances. Let’s name stages and scholarships after them.

We aren’t just their descendants. We’re their witnesses. We’re their second chance to be seen — not as criminals, but as part of a legacy of queer survival and resistance.

They were here. And we still are.

Los Angeles Times Archive (May 21, 1914) – “Vice Squad Makes Many Arrests”

Los Angeles Times Archive (May 26, 1914) – “More Immoral Men Arrested in Long Beach”

Homestead Museum Blog – “The Long Beach Purity Raids of 1914 and Remembering LGBTQ History”

YouTube: Short Doc – The Long Beach Purity Raids

Enhanced with AI